Just when the forces of rationality had seemingly established a beachhead in the public health domain, they’re back on defense again, as the CDC declares vaccinated and unvaccinated people should wear masks indoors in areas of the country experiencing high transmission, and every schoolchild should be condemned to wear a mask all day long.

The moves, which come in response to surging case counts, seem to demonstrate an impulse that animates many questionable government policies: "We have to do something," regardless of whether that something can be reasonably expected to have a material impact on the problem at hand.

Most public and media discussion of mask policy reflects a foundational assumption that may well be false—namely, that widespread, all-purpose mask-wearing has had any meaningful impact on slowing the spread.

Intuition tells us covering our faces must be worthwhile. After all, if the virus is emitted from our noses and mouths, covering those openings has to make a big difference, right?

That gut feeling misleads us, though, because we tend to only think of the virus in terms of visible, tangible droplets masks can absorb. Indeed, the initial scientific consensus held that Covid-19 was exclusively transmitted by droplets, prompting the emphasis on distancing six feet from each other—room enough for gravity to pull those droplets out of the air.

That exclusive-droplet-transmission consensus proved wrong.

We now know Covid-19 is spread to a great extent via aerosols—a term that describes particles so small they can easily float along in the air, traveling well beyond six feet. Even that description fails to convey how unfathomably small Covid-19 viral particles actually are—and why masks are a mismatch.

How small are they? As little as 20 nanometers. That means the "material gaps in blue surgical masks are up to 1,000 times"” as large as a Covid-19 viral particle, according to Colin Axon, who has advised the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE).

Gaps in typical cloth masks can be 5,000 times the size…to say nothing of all that air that’s merely redirected past masks’ edges when we exhale.

"All around the world you can look at mask mandates and superimpose on infection rates, you cannot see that mask mandates made any effect whatsoever," said Axon to The Telegraph.

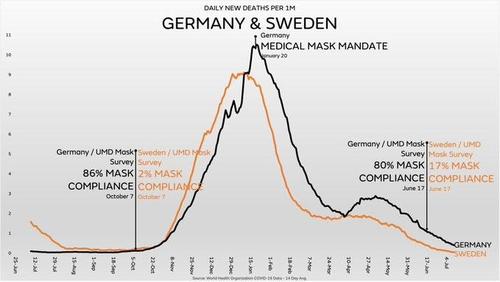

While there are many illustrations of that conclusion, perhaps none is more vivid than a comparison of Sweden—which, as a society, never went all-in on masking—and Germany, whose government in January went beyond merely requiring "face coverings" and mandated the use of medical-grade masks.

Despite Sweden’s sharply lower use of masks—and a much more relaxed approach in general—the country’s 12-month experience is essentially indistinguishable from what’s observed in Germany. Rather, one sees a force of nature taking its seasonal course.

"The best thing you can say about any mask is that any positive effect they do have is too small to be measured," said Axon, a Brunel University (London) lecturer in engineering who notes that "when the particle enters another body, it returns to a biomedical issue, but the mask debate is about the particle journey," where his knowledge applies.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom’s experience delivers a one-two punch. First, there’s no indication the imposition of mask mandates slowed transmission, which marched along in seasonal fashion. Second, the recent reopening of the country and lifting of mask mandates amusingly coincided with the beginning of a steep reversal of the summer surge in cases.

No comments:

Post a Comment