Faults crisscross California, producing deadly earthquakes.

But whenever the ground shakes, the first thought always turns to the mightiest and most dangerous fault: the San Andreas.

This is the 730-mile monster capable of producing the Big One, the fault famous enough to be the main character in a hit disaster movie.

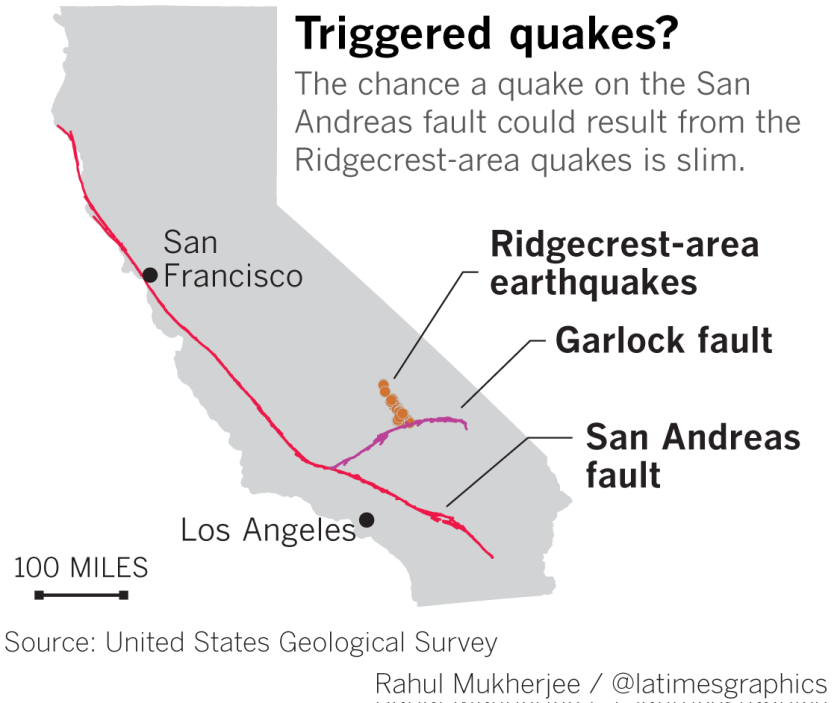

Scientists knew almost immediately that two large quakes that hit near Ridgecrest earlier this month did not come from the San Andreas.

But ever since, they’ve been studying whether the quakes could cause more seismic activity from other faults — including the San Andreas nearly 100 miles away.

A new calculation conducted in recent weeks at the U.S. Geological Survey showed that there’s an extremely remote chance the San Andreas could be triggered from the Ridgecrest quakes.

But the fault remains a source of constant anxiety, especially when ground moves. Previous quakes on the San Andreas were triggered by earlier nearby temblors. The great magnitude 7.8 quake in 1857 that ruptured 225 miles of the fault between Monterey County to the Cajon Pass in San Bernardino County was preceded by a pair of smaller quakes one and two hours earlier.

Earthquakes in Southern California in 1992, 2001, 2009 and 2016 all sparked concerns from scientists they could trigger a major quake on the San Andreas. In some of those cases, officials even issued a public warning of heightened seismic risk. For example, after the twin quakes in Landers and Big Bear in 1992, state officials announced there was a 50% chance of another big temblor in the coming days.

“We know that earthquakes can trigger other faults, even hundreds of miles away,” said USGS research geophysicist Morgan Page. “On one hand, the probability may go up. But it’s not a big increase compared to the risk we have year to year from the San Andreas, living in California.”

The southern San Andreas is quite dangerous on its own and can rupture without any nudging from a distant Mojave Desert fault. And it’s accumulating seismic stress so fast that even if it did rupture soon, scientists would probably spend the rest of their careers arguing over whether the July quakes had anything to do with it, said USGS research geologist Kate Scharer.

A big quake on the San Andreas would be devastating. The U.S. Geological Survey published a hypothetical scenario of a magnitude 7.8 earthquake on the San Andreas fault that could kill 1,800 people, injure 5,000, displace some 500,000 to 1 million people from their homes and hobble the region economically for a generation. That quake would send strong shaking into Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, Kern and Ventura counties almost simultaneously.

“There’s plenty of accumulated strain there,” Scharer said. “It’s the highest hazard fault, and it was before the [Ridgecrest] earthquake, and it will continue to be after the earthquake.

“It’s been quiet for so long.”

The seismic strain can be detected by GPS satellites — Mission Viejo in Orange County, on the southwest side of the San Andreas, can be seen scooting every year to the northwest, while Twentynine Palms in the Mojave Desert, on the other side of the fault, can be seen moving to the southeast, relatively speaking.

But along most parts of the San Andreas, the ground is not creeping. It’s stuck for long periods of time, and sooner or later, it needs to move in a huge quake to catch up with the rest of the continental plate. On average, there’s about 12 feet of movement per century along the 730-mile San Andreas fault system between Point Arena in Mendocino County and the Mexican border.

The amount of moved earth in a magnitude 7.8 quake can be eye-popping. In a remote section of Desert Hot Springs near Palm Springs, a couple holding hands across the San Andreas during such a megaquake would suddenly be separated as much as 30 feet, almost the entire length of a city bus, Scharer has said.

No comments:

Post a Comment